“This weekend at AMA I felt like I was equal… I did not feel like I was the ‘queer’ girl singing… I just felt like I was making great music and that was the most important part.” — Becca Mancari

What does female representation look like in a growing genre like Americana?

Every year, the Americana Music Association (AMA) holds AmericanaFest to showcase the artists on their radio charts, which specialize in roots music (Singer-songwriter, Folk, Bluegrass, Traditional, etc.) that does not fit into the mainstream pop/rock or popular country categories. While diverse representation was far from perfect at this Nashville roots music festival, especially in terms of minority and queer representation, AmericanaFest reported 90 female acts and 120 male acts this year, which is much closer to 50:50 than most festivals on the circuit. Really, there was a conscious, heartening effort to celebrate female artists at the festival — a few of whom were generous enough to talk about what it’s like to be an up-and-coming female in Americana, and in the music industry as a whole.

First, let’s start with Michaela Anne and her song “Bright Lights and the Fame.” Written in response to the Hank Williams’ song “Ramblin’ Man,” Michaela Anne wrote the song from the perspective of a woman left at home with the kids while her man goes out ramblin’.

“In the country world there are a lot of strong females, but it is so male [songwriter] dominated, especially the old stuff…[so this song is] a story that you don’t hear all the time…You always hear the ‘I’m a wanderin’ cowboy’ [story] but what about what is typically considered the more mundane?,” Michaela Anne said.

Michaela Anne performed the song during her showcase at AmericanaFest 2016 to an exuberant crowd who seemed thirsty for this sort of female perspective. By featuring artists like Michaela Anne, Americana takes steps to quench that thirst and reverse mainstream music’s habit of using women as sexualized mouthpieces for male songwriters.

“It has been incredible to see how much respect women get as songwriters now,” said roots songwriter Becca Mancari, who also performed at AmericanaFest. “For so long women have been focused on but often times for their looks and not the quality of their songwriting. That is changing, though it’s still an uphill fight.”

“Women are owning music right now,” country-punk artist Lydia Lovelessechoed, “[We’ve] spent so long listening to slighted dudes sing about a ‘devil woman,’ I’m ready to listen to another kind of feeling.”

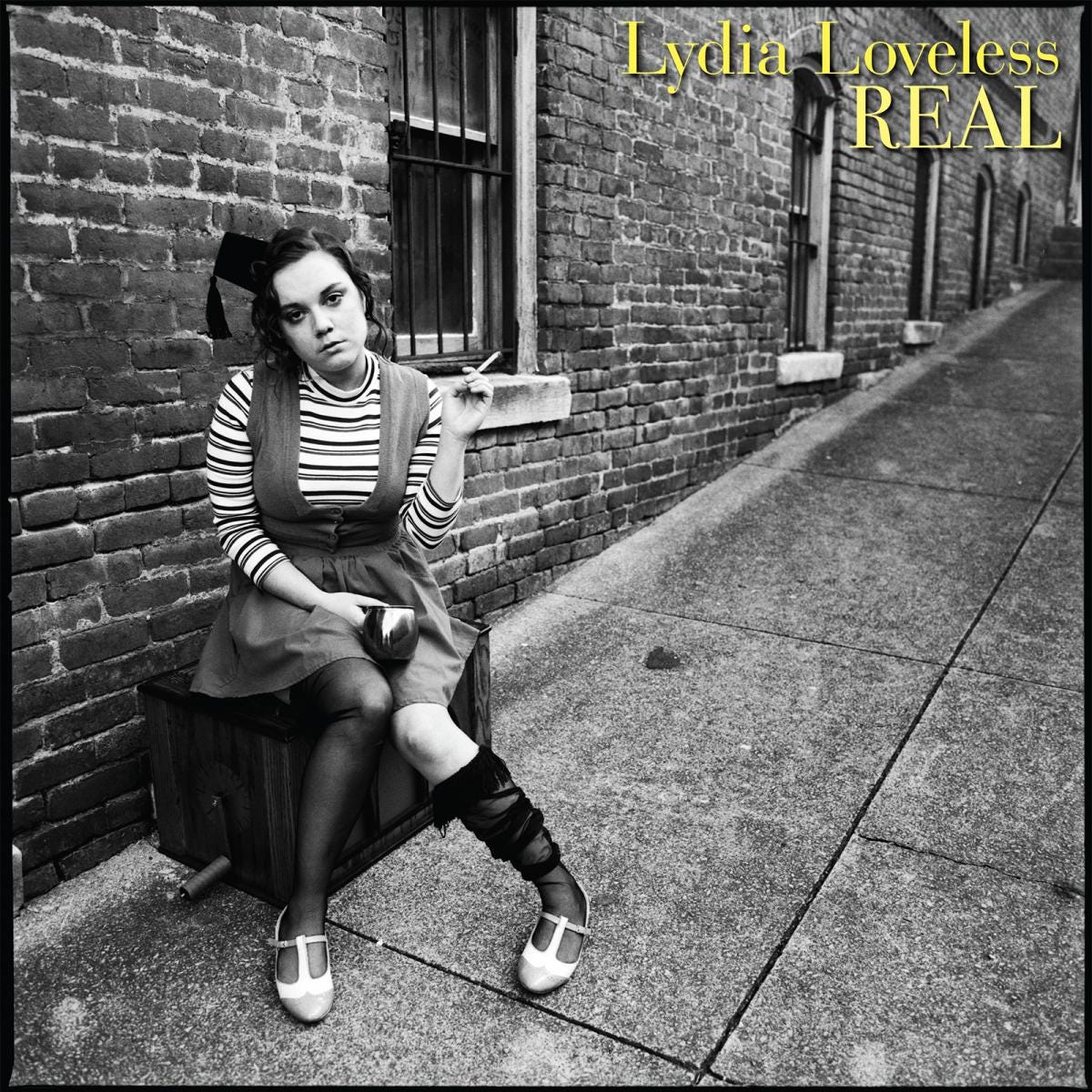

At this year’s AmericanaFest, Loveless performed tracks off her newest album Real, a rough-edged album that takes a candid look at romance and relationships. Loveless has always been known for this sort of honesty in the Americana community, and even through controversial songs like 2011’s “Jesus was a Wino,” she’s been encouraged and embraced by the community.

Mancari has been similarly welcomed for her candidness, especially notable because she is queer.

“This weekend at AMA I felt like I was equal… I did not feel like I was the “queer” girl singing… I just felt like I was making great music and that was the most important part. I mean…One song I have out called ‘Summertime Mama’ is about having a crush on a woman in town from afar, and as a queer woman I am so thankful that Lightning 100 (an independent radio station here in Nashville, and an AMA chart reporter) is playing it,” she said.

Undoubtedly, more space is being made for female narratives in Americana. But, it’s a slow, tenuous process. There is still much farther to go. Even the women who feel positive about female representation roots music note music industry sexism creeping in several ways.

“There’s still this feeling that there’s only so much room for a few select women. Or if you have a show where there’s three women, it’s always a ‘Ladies Night,’” said Michaela Anne.

Former contestant from The Voice, Sarah Potenza, also commented on the utter lack of female freelance musicians in much of Nashville, where a large chunk of roots music is recorded.

“I’ve only ever played with one female bass player here in Nashville,” she said, “The ratio of male to female freelance musicians, excluding front-women with their own bands, has got to be ridiculous, probably something like 1 to 30,” Potenza said.

In fact, AMA reported only 10 of the bands on the roster in 2016 had female musicians in them, outside of bands with front-women. This, as Michaela Anne said, only continues to narrow the list of “acceptable” roles women are allowed to have in music.

“I always say that even if it’s possible for women to do what they want they aren’t going to actually be it if there aren’t equal examples. It’s harder for females to learn that that’s an actual option without role models. That’s a deeply subconscious thing even if someone tells a girl ‘you can be whatever you want,” Michaela Anne said.

This applies not only to a female’s role in the band, but also what they can look like. It should be noted that many of the woman artists on the Americana charts are slender and young and white. (Racial representation is especially dismal: there were only a small amount of black artists showcased at the festival this year, and there’s only a handful of non-white artists on the AMA charts in general.) This comment isn’t meant to diminish thin, white women or their talent — but to point out that normative ideas of “beautiful” still have weight when it comes to success in Americana.

Sarah Potenza is a size 16, in her late thirties, and, for Americana, has an uncharacteristic husky-blues voice. She said, “I think I would have an easier time as a guy, I would have an easier time. Even if I was overweight and I was a guy I would have an easier time, especially with the voice I have.”

She raises an interesting point — the appearances of male musicians versus females is much more varied, suggesting that appearance isn’t considered to the same degree when it comes to signing them and promoting their music. In Americana in particular, males can wear weight and age as a badge of “authenticity” in a way women cannot.

“Big men are often very successful because people love a ‘big teddy bear.’ Nobody is like, ‘oh, she’s like a big sexy bossy lady. She’s just curvy and her visible belly outline is hot!” Nobody is really feeling that, so I think it’s harder,’” Potenza says.

To be fair, Potenza did go on to comment that the red carpet for the AMA awards, which happens the first night of the festival, did show Americana to be less ageist than she had thought. In fact, many of the matriarchs of the genre — like Emmylou Harris, Bonnie Raitt, and Shawn Colvin — were celebrated on the red carpet, brought on stage to perform, and award recipients.

Yet still, up-and-coming females in Americana have felt the sexist beauty standards of the industry creeping up on them, whether that be about their age or size.

“Sometimes I wonder if putting on a dress and looking the sexy part would help my career,” Mancari said. Lydia Loveless too, said, “I think it’s a lot harder to cross-over genres as a woman, because people want you to be this little doll — fit in this box.”

So no, Americana as a genre is far from perfect. It’s still a product of the world we live in, a world where presidential candidates can threaten women’s safety and call it “locker room talk,” where women’s appearances are still judged before their brains and talent, and where the patriarchal business structure of the music industry leaves decision-making power up to older, caucasian, cis-gender males. But what is different about Americana as a genre, as witnessed at AmericanaFest and through correspondence with those involved in the Americana Music Association, is that it is affording most women the luxury of telling their stories, despite the broader music industry’s attempts to mold them to pervasive standards. So perhaps, despite some noticeable pitfalls, Americana is trying to fight the good fight.

Originally published on Amy Poehler’s Smart Girls.